The .NET Core 3.0 SDK includes many more templates out-of-the-box than previous versions. In this post I compare some of the different templates used by ASP.NET Core 3 apps, and look at some of the new helper methods used for service and middleware configuration in ASP.NET Core 3.0.

I'm only looking at the ASP.NET Core templates in this post:

- ASP.NET Core Empty template

- ASP.NET Core Web API template

- ASP.NET Core Web App (Model-View-Controller) template

- ASP.NET Core Web App (Razor) template

There are many more templates than these that I'm not covering here - Blazor templates, client-side templates, worker templates - you can see them all by running dotnet new list!

The ASP.NET Core Empty template

You can create the "empty" template by running dotnet new web, and it's pretty, well, empty. You get the standard Program.cs configuring the Generic Host, and a sparse Startup.cs shown below:

public class Startup

{

public void ConfigureServices(IServiceCollection services) { }

public void Configure(IApplicationBuilder app, IWebHostEnvironment env)

{

if (env.IsDevelopment())

{

app.UseDeveloperExceptionPage();

}

app.UseRouting();

app.UseEndpoints(endpoints =>

{

endpoints.MapGet("/", async context =>

{

await context.Response.WriteAsync("Hello World!");

});

});

}

}

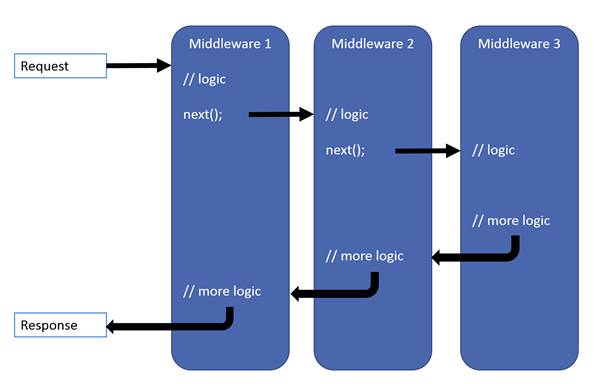

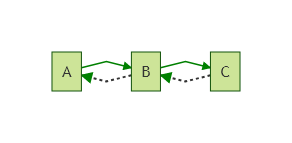

The main difference compared to ASP.NET Core 2.x apps is the conspicuous use of endpoint routing. This was introduced in 2.2, but could only be used for MVC controllers. In 3.0, endpoint routing is the preferred approach, with the most basic setup provided here.

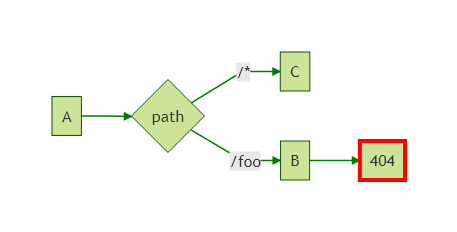

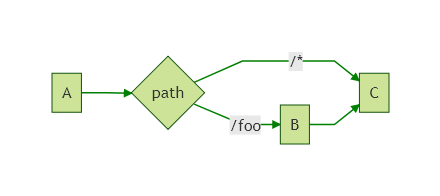

Endpoint routing separates the process of selecting which "endpoint" will execute from the actual running of that endpoint. An endpoint consists of a path pattern, and something to execute when called. It could be an MVC action on a controller or it could be a simple lambda, as shown in this example where we're creating an endpoint using MapGet() for the path /.

The UseRouting() extension method is what looks at the incoming request and decides which endpoint should execute. Any middleware that appears after the UseRouting() call will know which endpoint will run eventually. The UseEndpoints() call is responsible for configuring the endpoints, but also for executing them.

If you're new to endpoint routing, I suggest taking a look at this post by Areg Sarkissian, or this post by Jürgen Gutsch.

The ASP.NET Core Web API template

The next most complex template is the Web API template, created by running dotnet new webapi. This includes a simple [ApiController] Controller with a single Get method. The Startup.cs file (shown below) is slightly more complex than the empty template, but includes many of the same aspects.

public class Startup

{

public Startup(IConfiguration configuration)

{

Configuration = configuration;

}

public IConfiguration Configuration { get; }

public void ConfigureServices(IServiceCollection services)

{

services.AddControllers();

}

public void Configure(IApplicationBuilder app, IWebHostEnvironment env)

{

if (env.IsDevelopment())

{

app.UseDeveloperExceptionPage();

}

app.UseHttpsRedirection();

app.UseRouting();

app.UseAuthorization();

app.UseEndpoints(endpoints =>

{

endpoints.MapControllers();

});

}

}

It isn't used in the default template, but the IConfiguration is injected in the constructor in this template. In any real application you'll almost certainly need access to this to configure your services, so it makes sense.

In ConfigureServices, there's a call to an extension method, AddControllers(), which is new in ASP.NET Core 3.0. In 2.x, you would typically call services.AddMvc() for all ASP.NET Core applications. However, this would configure the services for everything MVC used, such as Razor Pages and View rendering. If you're creating a Web API only, then those services were completely superfluous.

To get around this, I showed in a previous post how you could create a stripped down version of AddMvc(), only adding the things you really need for creating Web APIs. The AddControllers() extension method now does exactly that - it adds the services required to use Web API Controllers, and nothing more. So you get Authorization, Validation, formatters, and CORS for example, but nothing related to Razor Pages or view rendering. For the full details of what's included see the source code on GitHub.

The middleware pipeline is fleshed out a little compared to the empty template. We have the developer exception page when running in the Development environment, but note there's no exception page in other environments. That's because it's expected that the ApiController will transform errors to the standard Problem Details format.

Next is the HTTPS redirection middleware, which ensures requests are made over a secure domain (definitely a best practice). Then we have the Routing middleware, early in the pipeline again, so that subsequent middleware can use the selected endpoint when deciding how to behave.

The Authorization middleware is new in 3.0, and is enabled largely thanks to the introduction of endpoint routing. You can still decorate your controller actions with [Authorize] attributes, but now the enforcement of those attributes occurs here. The real advantage is that you can apply authorization policies to non-MVC endpoints, which previously had to be handled in a manual, imperative manner.

Finally, the API controllers are mapped by calling endpoints.MapControllers(). This only maps controllers that are decorated with routing attributes - it doesn't configure any conventional routes.

The ASP.NET Core Web App (MVC) template

The MVC template (dotnet new mvc) includes a few more pieces than the Web API template, but it's been slimmed down slightly from its equivalent in 2.x. There's only a single controller, the HomeController, the associated Views, and required shared Razor templates.

Startup.cs is very similar to the Web API template, with just a few differences I discuss below:

public class Startup

{

public Startup(IConfiguration configuration)

{

Configuration = configuration;

}

public IConfiguration Configuration { get; }

public void ConfigureServices(IServiceCollection services)

{

services.AddControllersWithViews();

}

public void Configure(IApplicationBuilder app, IWebHostEnvironment env)

{

if (env.IsDevelopment())

{

app.UseDeveloperExceptionPage();

}

else

{

app.UseExceptionHandler("/Home/Error");

app.UseHsts();

}

app.UseHttpsRedirection();

app.UseStaticFiles();

app.UseRouting();

app.UseAuthorization();

app.UseEndpoints(endpoints =>

{

endpoints.MapControllerRoute(

name: "default",

pattern: "{controller=Home}/{action=Index}/{id?}");

});

}

}

In place of the AddControllers() extension method, this time we have AddControllersWithViews. As you might expect, this adds the MVC Controller services that are common to both Web API and MVC, but also adds the services required for rendering Razor views.

As this is an MVC app, the middleware pipeline includes the Exception handler middleware for environments outside of Development, and also adds the HSTS and HTTPS redirection middleware, the same as for 2.2.

Next up is the static file middleware, which is placed before the routing middleware. This ensures that routing doesn't need to happen for every static file request, which could be quite frequent in an MVC app.

The only other difference from the Web API template is the registration of the MVC controllers in the endpoint routing middleware. In this case a conventional route is added for the MVC controllers, instead of the attribute routing approach that is typical for Web APIs. Again, this is similar to the setup in 2.x, but adjusted for the endpoint routing system.

ASP.NET Core Web App (Razor) template

Razor Pages was introduced in ASP.NET Core 2.0 as a page-based alternative to MVC. For many apps, Razor Pages provides a more natural model than MVC, However it's fundamentally built on top of the MVC infrastructure, so the Startup.cs from dotnet new webapp looks very similar to the MVC version:

public class Startup

{

public Startup(IConfiguration configuration)

{

Configuration = configuration;

}

public IConfiguration Configuration { get; }

public void ConfigureServices(IServiceCollection services)

{

services.AddRazorPages();

}

public void Configure(IApplicationBuilder app, IWebHostEnvironment env)

{

if (env.IsDevelopment())

{

app.UseDeveloperExceptionPage();

}

else

{

app.UseExceptionHandler("/Error");

app.UseHsts();

}

app.UseHttpsRedirection();

app.UseStaticFiles();

app.UseRouting();

app.UseAuthorization();

app.UseEndpoints(endpoints =>

{

endpoints.MapRazorPages();

});

}

}

The first change in this file is the replacement of AddControllersWithViews() with AddRazorPages(). As you might expect, this adds all of the additional services required for Razor Pages. Interestingly it does not add the services required for using standard MVC controllers with Razor Views. If you want to use both MVC and Razor Pages in your app, you should continue to use the AddMvc() extension method.

The only other change to Startup.cs is to replace the MVC endpoint with the Razor Pages endpoint. As with the services, if you wish to use both MVC and Razor Pages in your app, then you'll need to map both endpoints, e.g.

app.UseEndpoints(endpoints =>

{

endpoints.MapControllers(); // Map attribute-routed API controllers

endpoints.MapDefaultControllerRoute(); // Map conventional MVC controllers using the default route

endpoints.MapRazorPages();

});

Summary

This post provided a brief overview of the Startup.cs files created by the various ASP.NET Core templates using the .NET Core 3.0 SDK. Each template adds a little extra to the previous one, providing a few extra features. In many ways the templates are very similar to those from .NET Core 2.x. The biggest new features are the ability to more easily include the minimal number of MVC services required by your app, and the new endpoint routing, which is the standard routing approach in .NET Core 3.0