According to the definition by Gartner: “Microservice is a tightly scoped, strongly encapsulated, loosely coupled, independently deployable, and independently scalable application component.”

The goal of the microservices is to sufficiently decompose/decouple the application into loosely coupled microservices/modules in contrast to monolithic applications where modules are highly coupled and deployed as a single big chunk. This will be helpful due to the following reasons:

- Each microservice can be deployed, upgraded, scaled, maintained, and restarted independent of sibling services in the application.

- Agile development & agile deployment with an autonomous cross-functional team.

- Flexibility in using technologies and scalability.

Different loosely coupled services are deployed based upon their own specific needs where each service has its fine-grained APIs model to serve different clients (Web, Mobile, and 3rd party APIs).

Client to Microservices connections

While thinking of the client directly communicating with each of the deployed microservices, the following challenges should be taken into consideration:

- In the case where microservice is exposing fine-grained APIs to the client, the client should request to each microservice. In a typical single page, it may be required for multiple server round trips in order to fulfill the request. This may be even worse for low network operating devices such as mobile.

- Diverse communication protocol (such as gRpc, thrift, REST, AMQP e.t.c) existing in the microservices makes it challenging and bulky for the client to adopt all those protocols.

- Common gateway functionalities (such as authentication, authorization, logging) have to be implemented in each microservice.

- It will be difficult to make changes in microservices without disrupting client connection. For e.g while merging or dividing microservices, it may be required to recode the client section.

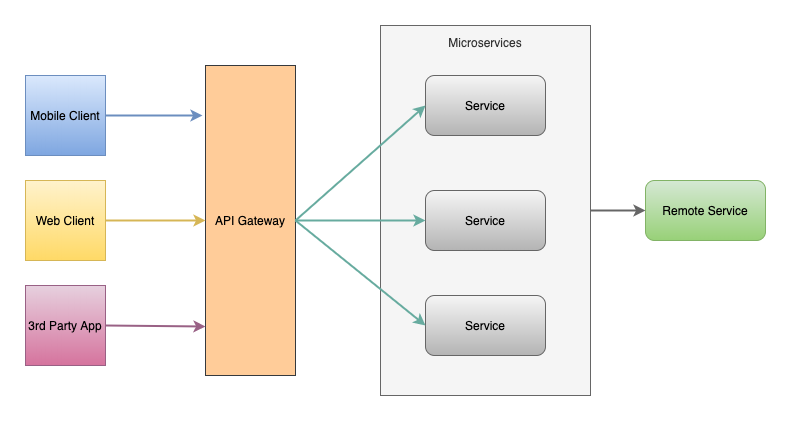

API Gateway

To address the above-mentioned challenges, an additional layer is introduced that sits between the client and the server acting as a reverse proxy routing request from the client to the server. Similar to the facade pattern of Object-Oriented Design, it provides a single entry point to the APIs encapsulating the underlying system architecture which is called API Gateway.

In short, it behaves precisely as API management but it is important not to confuse API management with API Gateway.

Functionalities of API Gateway:

Routing

Encapsulating the underlying system and decoupling from the clients, the gateway provides a single entry point for the client to communicate with the microservice system.

Offloading

API gateway consolidates the edge functionalities rather than making every microservices implementing them. Some of the functionalities are:

- Authentication and authorization

- Service discovery integration

- Response caching

- Retry policies, circuit breaker, and QoS

- Rate limiting and throttling

- Load balancing

- Logging, tracing, correlation

- Headers, query strings, and claims transformation

- IP whitelisting

- IAM

- Centralized Logging (transaction ID across the servers, error logging)

- Identity Provider, Authentication and Authorization

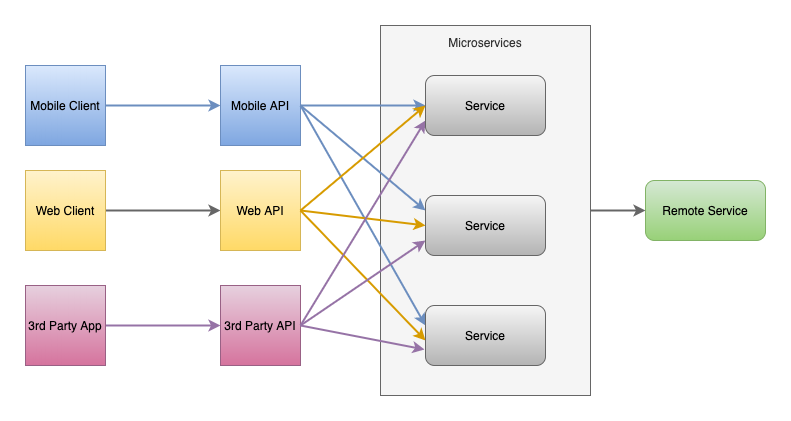

Backend for Frontend (BFF) pattern

It is a variation of the API Gateway pattern. Rather than a single point of entry for the clients, it provides multiple gateways based upon the client. The purpose is to provide tailored APIs according to the needs of the client, removing a lot of bloats caused by making generic APIs for all the clients.

How many BFFs do you need?

The base concept of BFF is developing niche backends for each user experience. The guideline by Phil Calçado is ‘one experience, one BFF’. If the requirements across clients (IOS client, android client, a web browser e.t.c) vary significantly and the time to market of a single proxy or API becomes problematic, BFFs are a good solution. It should also be noted that the more complex design requires a complex setup.

GraphQL and BFF

GraphQL is a query language for your API. Phil Calçado presents in this article that BFF and GraphQL are related but not mutually exclusive concepts. He adds that BFFs are not about the shape of your endpoints, but about giving your client applications autonomy where you can build your GraphQL APIs as many BFFs or as an OSFA (one-size-fits-all) API.

Notable API Gateways

Netflix API Gateway: Zuul

The Netflix streaming service available on more than 1000 different device types (televisions, set‑top boxes, smartphones, gaming systems, tablets, e.t.c) handing over 50,000 requests per second during peak hours, found substantial limitations in OSFA (one-size-fits-all) REST API approach and used the API Gateway tailored for each device.

Zuul 2 at Netflix is the front door for all requests coming into Netflix’s cloud infrastructure. Zuul 2 significantly improves the architecture and features that allow our gateway to handle, route, and protect Netflix’s cloud systems, and helps provide our 125 million members the best experience possible.

Amazon API Gateway

AWS provides fully managed service for creating, publishing, maintaining, monitoring, and securing REST, HTTP, and WebSocket where developers can create APIs that access AWS or other web services, as well as data stored in the AWS Cloud.

Kong API Gateway

Kong Gateway is an open-source, lightweight API gateway optimized for microservices, delivering unparalleled latency performance and scalability. If you just want the basics, this option will work for you. It is scalable easily horizontally by adding more nodes. It supports large and variable workloads with very low latency.

Other API Gateways

Choosing the right API gateway

Some of the common baseline for evaluation criteria include simplicity, open-source vs propriety, scalability & flexibility, security, features, community, administrative (support, monitoring & deployment), environment provisioning(installation, configuration, hosting offering), pricing, and documentation.

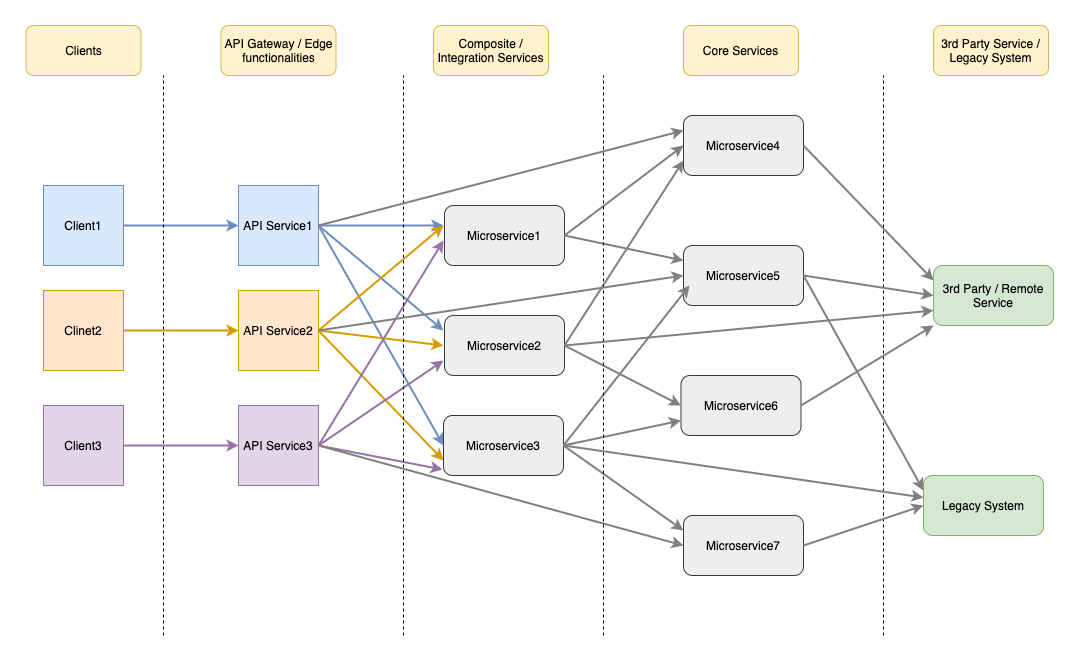

API Composition / Aggregation

Some API requests in API Gateway map directly to single service API which can be served by routing request to the corresponding microservice. However, in the case of complex API operations that requires results from several microservices can be served by API composition/aggregation (a scatter-gather mechanism). In case of dependency of one another service where synchronous communication is required, the chained composition pattern has to be followed. The composition layer has to support a significant portion of ESB/integration capabilities such as transformations, orchestration, resiliency, and stability patterns.

A root container is deployed with the special distributor and aggregator functionalities (or microservices). The distributor is responsible for breaking down into granular tasks and distributing those tasks to microservice instances. The aggregator is responsible for aggregating the results derived by business workflow from composed microservice.

API Gateway and Aggregation

API gateway with added features results in overambitious gateways that encourage designs that continue to be difficult to test and deploy. It is highly recommended to avoid aggregation and data transformation in the API Gateway. Domain smarts are better suited to be done in application code that follows the defined software development practices. Netflix API Gateway, Zuul 2 removed a lot of the business logic from Gateway that they had in Zuul to origin systems. For more details, refer here.

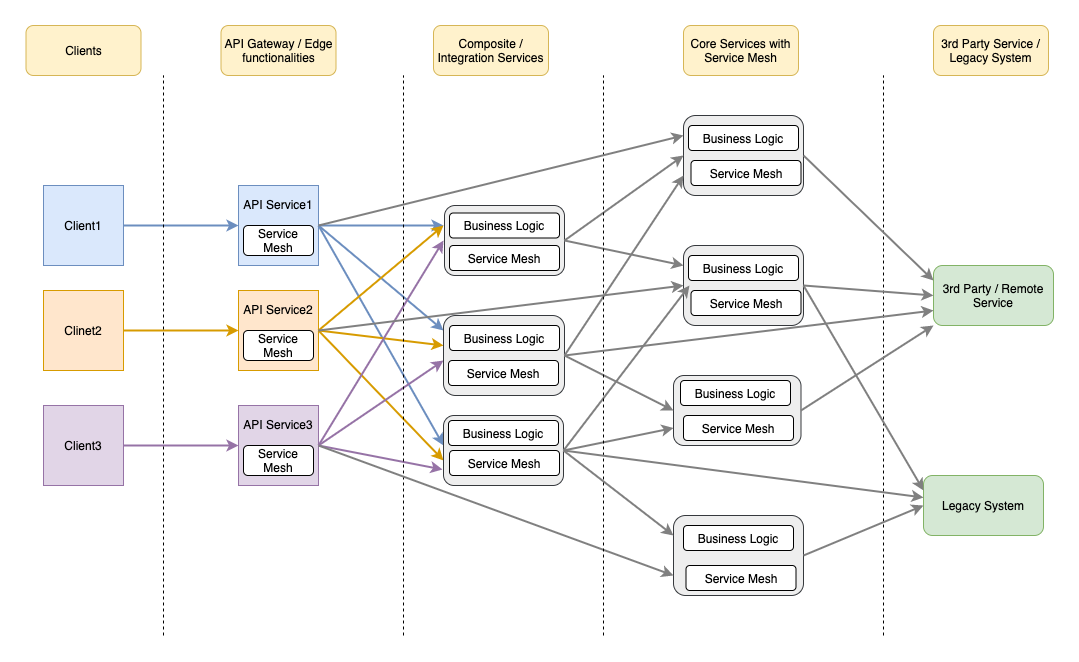

Service Mesh and API Gateway

Service mesh in microservices is a configurable network infrastructure layer that handles interprocess communication. This is akin to what is often termed as sidecar proxy or sidecar gateway. It provides a lot of functionalities such as:

- Load Balancing

- Service Discovery

- Health Checks

- Security

On the surface, it appears as though API gateways and service meshes solve the same problem and are therefore redundant. They do solve the same problem but in different contexts. API gateway is deployed as a part of a business solution that is discoverable by the external clients handling north-south traffic(face external client), however, service mesh handles east-west traffic (among different microservices).

Implementing service mesh avoids the resilient communication pattern such as circuit breakers, discovery, health checks, service observability in your own code. For a small number of microservices, alternative strategies for failure management should be considered as service mesh integration may overkill you. For a larger number of microservices, it will be beneficial.

Combining these two technologies can be a powerful way to ensure application uptime and resiliency while ensuring your applications are easily consumable. Viewing two as a contemporary can be a bad idea and it is better to view two as being complementary to one another in deployments that involve both microservices and APIs.

Considerations for API Gateway implementation:

- Possible single point of failure or bottleneck.

- Increase in response time due to additional network hop through API Gateway and risk of complexity.

References:

- https://microservices.io/index.html

- https://docs.microsoft.com/en-us/azure/architecture/

- https://github.com/wso2/reference-architecture/blob/master/api-driven-microservice-architecture.md

- https://tsh.io/blog/design-patterns-in-microservices-api-gateway-bff-and-more/

- https://www.infoq.com/articles/service-mesh-ultimate-guide/

- https://samnewman.io/patterns/architectural/bff/

- https://netflixtechblog.com/