As a good JavaScript developer, you strive to write clean, healthy, and maintainable code. You solve interesting challenges that, while unique, don’t necessarily require unique solutions. You’ve likely found yourself writing code that looks similar to the solution of an entirely different problem you’ve handled before. You may not know it, but you’ve used a JavaScript design pattern. Design patterns are reusable solutions to commonly occurring problems in software design.

During any language’s lifespan, many such reusable solutions are made and tested by a large number of developers from that language’s community. It is because of this combined experience of many developers that such solutions are so useful because they help us write code in an optimized way while at the same time solving the problem at hand.

The main benefits we get from design patterns are the following:

- They are proven solutions: Because design patterns are often used by many developers, you can be certain that they work. And not only that, you can be certain that they were revised multiple times and optimizations were probably implemented.

- They are easily reusable: Design patterns document a reusable solution which can be modified to solve multiple particular problems, as they are not tied to a specific problem.

- They are expressive: Design patterns can explain a large solution quite elegantly.

- They ease communication: When developers are familiar with design patterns, they can more easily communicate with one another about potential solutions to a given problem.

- They prevent the need for refactoring code: If an application is written with design patterns in mind, it is often the case that you won’t need to refactor the code later on because applying the correct design pattern to a given problem is already an optimal solution.

- They lower the size of the codebase: Because design patterns are usually elegant and optimal solutions, they usually require less code than other solutions.

I know you’re ready to jump in at this point, but before you learn all about design patterns, let’s review some JavaScript basics.

A Brief History of JavaScript

JavaScript is one of the most popular programming languages for web development today. It was initially made as a sort of a “glue” for various displayed HTML elements, known as a client-side scripting language, for one of the initial web browsers. Called Netscape Navigator, it could only display static HTML at the time. As you might assume, the idea of such a scripting language led to browser wars between the big players in the browser development industry back then, such as Netscape Communications (today Mozilla), Microsoft, and others.

Each of the big players wanted to push through their own implementation of this scripting language, so Netscape made JavaScript (actually, Brendan Eich did), Microsoft made JScript, and so forth. As you can image, the differences between these implementations were great, so development for web browsers was made per-browser, with best-viewed-on stickers that came with a web page. It soon became clear that we needed a standard, a cross-browser solution which would unify the development process and simplify the creation of web pages. What they came up with is called

ECMAScript.

ECMAScript is a standardized scripting language specification which all modern browsers try to support, and there are multiple implementations (you could say dialects) of ECMAScript. The most popular one is the topic of this article, JavaScript. Since its initial release, ECMAScript has standardized a lot of important things, and for those more interested in the specifics, there is a detailed list of standardized items for each version of the ECMAScript available on Wikipedia. Browser support for ECMAScript versions 6 (ES6) and higher are still incomplete and have to be transpiled to ES5 in order to be fully supported.

What Is JavaScript?

In order to fully grasp the contents of this article, let’s make an introduction to some very important language characteristics that we need to be aware of before diving into JavaScript design patterns. If someone were to ask you “What is JavaScript?” you might answer somewhere in the lines of:

JavaScript is a lightweight, interpreted, object-oriented programming language with first-class functions most commonly known as a scripting language for web pages.

The aforementioned definition means to say that JavaScript code has a low memory footprint, is easy to implement, and easy to learn, with a syntax similar to popular languages such as C++ and Java. It is a scripting language, which means that its code is interpreted instead of compiled. It has support for procedural, object-oriented, and functional programming styles, which makes it very flexible for developers.

So far, we have taken a look at all of the characteristics which sound like many other languages out there, so let’s take a look at what is specific about JavaScript in regard to other languages. I am going to list a few characteristics and give my best shot at explaining why they deserve special attention.

JavaScript Supports First-class Functions

This characteristic used to be troublesome for me to grasp when I was just starting with JavaScript, as I came from a C/C++ background. JavaScript treats functions as first-class citizens, meaning you can pass functions as parameters to other functions just like you would any other variable.

function performOperation(a, b, cb) {

var c = a + b;

cb(c);

}

performOperation(2, 3, function(result) {

console.log("The result of the operation is " + result);

})

JavaScript Is Prototype-based

As is the case with many other object-oriented languages, JavaScript supports objects, and one of the first terms that comes to mind when thinking about objects is classes and inheritance. This is where it gets a little tricky, as the language doesn’t support classes in its plain language form but rather uses something called prototype-based or instance-based inheritance.

It is just now, in ES6, that the formal term class is introduced, which means that the browsers still don’t support this (if you remember, as of writing, the last fully supported ECMAScript version is 5.1). It is important to note, however, that even though the term “class” is introduced into JavaScript, it still utilizes prototype-based inheritance under the hood.

Prototype-based programming is a style of object-oriented programming in which behavior reuse (known as inheritance) is performed via a process of reusing existing objects via delegations that serve as prototypes. We will dive into more detail with this once we get to the design patterns section of the article, as this characteristic is used in a lot of JavaScript design patterns.

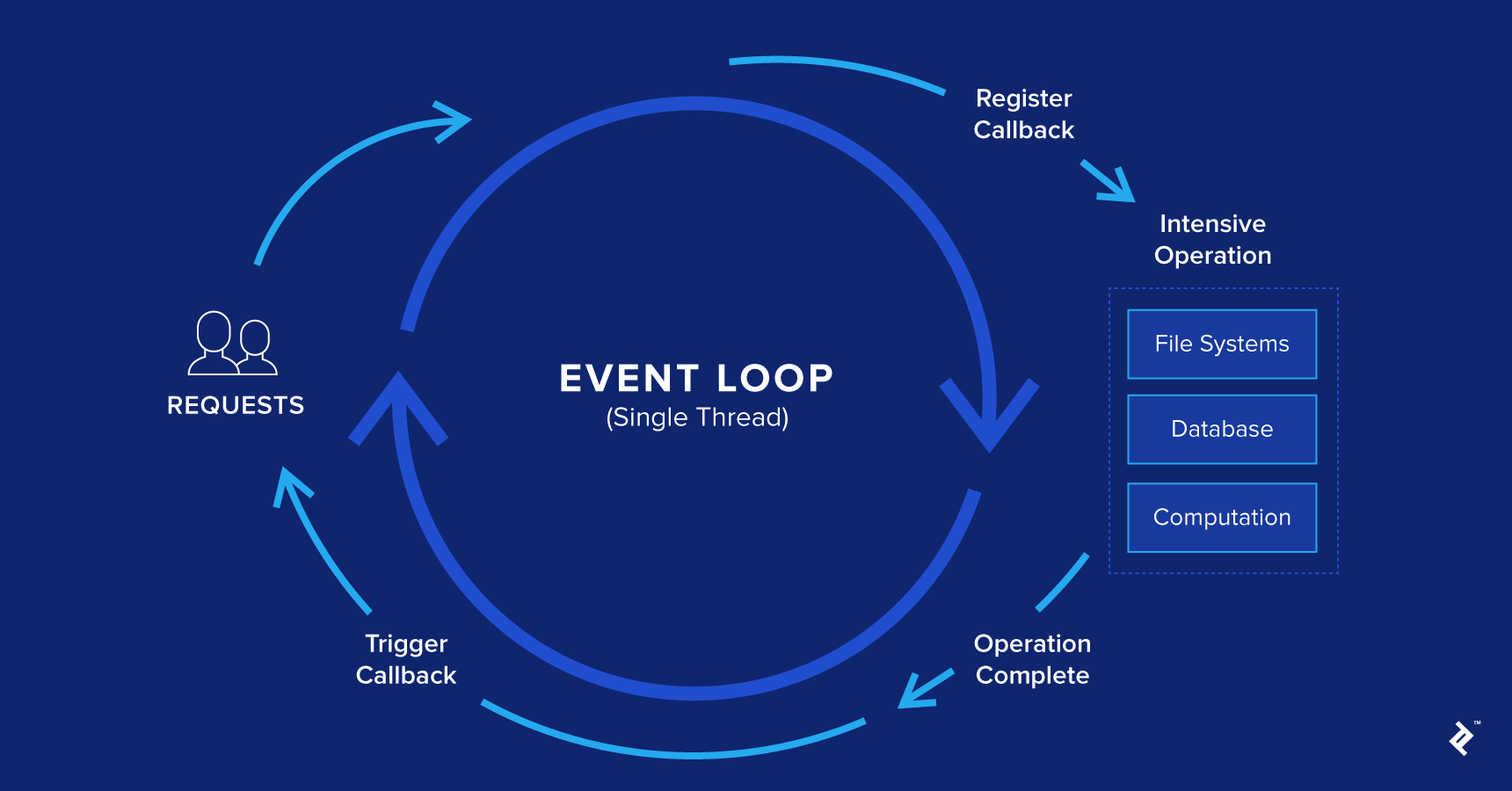

JavaScript Event Loops

If you have experience working with JavaScript, you are surely familiar with the term callback function. For those not familiar with the term, a callback function is a function sent as a parameter (remember, JavaScript treats functions as first-class citizens) to another function and gets executed after an event fires. This is usually used for subscribing to events such as a mouse click or a keyboard button press.

Each time an event, which has a listener attached to it, fires (otherwise the event is lost), a message is being sent to a queue of messages which are being processed synchronously, in a FIFO manner (first-in-first-out). This is called the event loop.

Each of the messages on the queue has a function associated with it. Once a message is dequeued, the runtime executes the function completely before processing any other message. This is to say, if a function contains other function calls, they are all performed prior to processing a new message from the queue. This is called run-to-completion.

while (queue.waitForMessage()) {

queue.processNextMessage();

}

The queue.waitForMessage() synchronously waits for new messages. Each of the messages being processed has its own stack and is processed until the stack is empty. Once it finishes, a new message is processed from the queue, if there is one.

You might have also heard that JavaScript is non-blocking, meaning that when an asynchronous operation is being performed, the program is able to process other things, such as receiving user input, while waiting for the asynchronous operation to complete, not blocking the main execution thread. This is a very useful property of JavaScript and a whole article could be written just on this topic; however, it is outside of the scope of this article.

What Are Design Patterns?

As I said before, design patterns are reusable solutions to commonly occurring problems in software design. Let’s take a look at some of the categories of design patterns.

Proto-patterns

How does one create a pattern? Let’s say you recognized a commonly occurring problem, and you have your own unique solution to this problem, which isn’t globally recognized and documented. You use this solution every time you encounter this problem, and you think that it’s reusable and that the developer community could benefit from it.

Does it immediately become a pattern? Luckily, no. Oftentimes, one may have good code writing practices and simply mistake something that looks like a pattern for one when, in fact, it is not a pattern.

How can you know when what you think you recognize is actually a design pattern?

By getting other developers’ opinions about it, by knowing about the process of creating a pattern itself, and by making yourself well acquainted with existing patterns. There is a phase a pattern has to go through before it becomes a full-fledged pattern, and this is called a proto-pattern.

A proto-pattern is a pattern-to-be if it passes a certain period of testing by various developers and scenarios where the pattern proves to be useful and gives correct results. There is quite a large amount of work and documentation—most of which is outside the scope of this article—to be done in order to make a fully-fledged pattern recognized by the community.

Anti-patterns

As a design pattern represents good practice, an anti-pattern represents bad practice.

An example of an anti-pattern would be modifying the Object class prototype. Almost all objects in JavaScript inherit from Object (remember that JavaScript uses prototype-based inheritance) so imagine a scenario where you altered this prototype. Changes to the Object prototype would be seen in all of the objects that inherit from this prototype—which would be most JavaScript objects. This is a disaster waiting to happen.

Another example, similar to one mentioned above, is modifying objects that you don’t own. An example of this would be overriding a function from an object used in many scenarios throughout the application. If you are working with a large team, imagine the confusion this would cause; you’d quickly run into naming collisions, incompatible implementations, and maintenance nightmares.

Similar to how it is useful to know about all of the good practices and solutions, it is also very important to know about the bad ones too. This way, you can recognize them and avoid making the mistake up front.

Design Pattern Categorization

Design patterns can be categorized in multiple ways, but the most popular one is the following:

- Creational design patterns

- Structural design patterns

- Behavioral design patterns

- Concurrency design patterns

- Architectural design patterns

Creational Design Patterns

These patterns deal with object creation mechanisms which optimize object creation compared to a basic approach. The basic form of object creation could result in design problems or in added complexity to the design. Creational design patterns solve this problem by somehow controlling object creation. Some of the popular design patterns in this category are:

- Factory method

- Abstract factory

- Builder

- Prototype

- Singleton

Structural Design Patterns

These patterns deal with object relationships. They ensure that if one part of a system changes, the entire system doesn’t need to change along with it. The most popular patterns in this category are:

- Adapter

- Bridge

- Composite

- Decorator

- Facade

- Flyweight

- Proxy

Behavioral Design Patterns

These types of patterns recognize, implement, and improve communication between disparate objects in a system. They help ensure that disparate parts of a system have synchronized information. Popular examples of these patterns are:

- Chain of responsibility

- Command

- Iterator

- Mediator

- Memento

- Observer

- State

- Strategy

- Visitor

Concurrency Design Patterns

These types of design patterns deal with multi-threaded programming paradigms. Some of the popular ones are:

- Active object

- Nuclear reaction

- Scheduler

Architectural Design Patterns

Design patterns which are used for architectural purposes. Some of the most famous ones are:

- MVC (Model-View-Controller)

- MVP (Model-View-Presenter)

- MVVM (Model-View-ViewModel)

In the following section, we are going to take a closer look at some of the aforementioned design patterns with examples provided for better understanding.

Design Pattern Examples

Each of the design patterns represents a specific type of solution to a specific type of problem. There is no universal set of patterns that is always the best fit. We need to learn when a particular pattern will prove useful and whether it will provide actual value. Once we are familiar with the patterns and scenarios they are best suited for, we can easily determine whether or not a specific pattern is a good fit for a given problem.

Remember, applying the wrong pattern to a given problem could lead to undesirable effects such as unnecessary code complexity, unnecessary overhead on performance, or even the spawning of a new anti-pattern.

These are all important things to consider when thinking about applying a design pattern to our code. We are going to take a look at some of the design patterns I personally found useful and believe every senior JavaScript developer should be familiar with.

Constructor Pattern

When thinking about classical object-oriented languages, a constructor is a special function in a class which initializes an object with some set of default and/or sent-in values.

Common ways to create objects in JavaScript are the three following ways:

var instance = {};

var instance = Object.create(Object.prototype);

var instance = new Object();

After creating an object, there are four ways (since ES3) to add properties to these objects. They are the following:

instance.key = "A key's value";

instance["key"] = "A key's value";

Object.defineProperty(instance, "key", {

value: "A key's value",

writable: true,

enumerable: true,

configurable: true

});

Object.defineProperties(instance, {

"firstKey": {

value: "First key's value",

writable: true

},

"secondKey": {

value: "Second key's value",

writable: false

}

});

The most popular way to create objects is the curly brackets and, for adding properties, the dot notation or square brackets. Anyone with any experience with JavaScript has used them.

We mentioned earlier that JavaScript doesn’t support native classes, but it does support constructors through the use of a “new” keyword prefixed to a function call. This way, we can use the function as a constructor and initialize its properties the same way we would with a classic language constructor.

function Person(name, age, isDeveloper) {

this.name = name;

this.age = age;

this.isDeveloper = isDeveloper || false;

this.writesCode = function() {

console.log(this.isDeveloper? "This person does write code" : "This person does not write code");

}

}

var person1 = new Person("Bob", 38, true);

var person2 = new Person("Alice", 32);

person1.writesCode();

person2.writesCode();

However, there is still room for improvement here. If you’ll remember, I mentioned previously that JavaScript uses prototype-based inheritance. The problem with the previous approach is that the method writesCode gets redefined for each of the instances of the Person constructor. We can avoid this by setting the method into the function prototype:

function Person(name, age, isDeveloper) {

this.name = name;

this.age = age;

this.isDeveloper = isDeveloper || false;

}

Person.prototype.writesCode = function() {

console.log(this.isDeveloper? "This person does write code" : "This person does not write code");

}

var person1 = new Person("Bob", 38, true);

var person2 = new Person("Alice", 32);

person1.writesCode();

person2.writesCode();

Now, both instances of the Person constructor can access a shared instance of the writesCode() method.

Module Pattern

As far as peculiarities go, JavaScript never ceases to amaze. Another peculiar thing to JavaScript (at least as far as object-oriented languages go) is that JavaScript does not support access modifiers. In a classical OOP language, a user defines a class and determines access rights for its members. Since JavaScript in its plain form supports neither classes nor access modifiers, JavaScript developers figured out a way to mimic this behavior when needed.

Before we go into the module pattern specifics, let’s talk about the concept of closure. A closure is a function with access to the parent scope, even after the parent function has closed. They help us mimic the behavior of access modifiers through scoping. Let’s show this via an example:

var counterIncrementer = (function() {

var counter = 0;

return function() {

return ++counter;

};

})();

console.log(counterIncrementer());

console.log(counterIncrementer());

console.log(counterIncrementer());

As you can see, by using the IIFE, we have tied the counter variable to a function which was invoked and closed but can still be accessed by the child function that increments it. Since we cannot access the counter variable from outside of the function expression, we made it private through scoping manipulation.

Using the closures, we can create objects with private and public parts. These are called modules and are very useful whenever we want to hide certain parts of an object and only expose an interface to the user of the module. Let’s show this in an example:

var collection = (function() {

var objects = [];

return {

addObject: function(object) {

objects.push(object);

},

removeObject: function(object) {

var index = objects.indexOf(object);

if (index >= 0) {

objects.splice(index, 1);

}

},

getObjects: function() {

return JSON.parse(JSON.stringify(objects));

}

};

})();

collection.addObject("Bob");

collection.addObject("Alice");

collection.addObject("Franck");

console.log(collection.getObjects());

collection.removeObject("Alice");

console.log(collection.getObjects());

The most useful thing that this pattern introduces is the clear separation of private and public parts of an object, which is a concept very similar to developers coming from a classical object-oriented background.

However, not everything is so perfect. When you wish to change the visibility of a member, you need to modify the code wherever you have used this member because of the different nature of accessing public and private parts. Also, methods added to the object after their creation cannot access the private members of the object.

Revealing Module Pattern

This pattern is an improvement made to the module pattern as illustrated above. The main difference is that we write the entire object logic in the private scope of the module and then simply expose the parts we want to be public by returning an anonymous object. We can also change the naming of private members when mapping private members to their corresponding public members.

var namesCollection = (function() {

var objects = [];

function addObject(object) {

objects.push(object);

}

function removeObject(object) {

var index = objects.indexOf(object);

if (index >= 0) {

objects.splice(index, 1);

}

}

function getObjects() {

return JSON.parse(JSON.stringify(objects));

}

return {

addName: addObject,

removeName: removeObject,

getNames: getObjects

};

})();

namesCollection.addName("Bob");

namesCollection.addName("Alice");

namesCollection.addName("Franck");

console.log(namesCollection.getNames());

namesCollection.removeName("Alice");

console.log(namesCollection.getNames());

The revealing module pattern is one of at least three ways in which we can implement a module pattern. The differences between the revealing module pattern and the other variants of the module pattern are primarily in how public members are referenced. As a result, the revealing module pattern is much easier to use and modify; however, it may prove fragile in certain scenarios, like using RMP objects as prototypes in an inheritance chain. The problematic situations are the following:

- If we have a private function which is referring to a public function, we cannot override the public function, as the private function will continue to refer to the private implementation of the function, thus introducing a bug into our system.

- If we have a public member pointing to a private variable, and try to override the public member from outside the module, the other functions would still refer to the private value of the variable, introducing a bug into our system.

Singleton Pattern

The singleton pattern is used in scenarios when we need exactly one instance of a class. For example, we need to have an object which contains some configuration for something. In these cases, it is not necessary to create a new object whenever the configuration object is required somewhere in the system.

var singleton = (function() {

var config;

function initializeConfiguration(values){

this.randomNumber = Math.random();

values = values || {};

this.number = values.number || 5;

this.size = values.size || 10;

}

return {

getConfig: function(values) {

if (config === undefined) {

config = new initializeConfiguration(values);

}

return config;

}

};

})();

var configObject = singleton.getConfig({ "size": 8 });

console.log(configObject);

var configObject1 = singleton.getConfig({ "number": 8 });

console.log(configObject1);

As you can see in the example, the random number generated is always the same, as well as the config values sent in.

It is important to note that the access point for retrieving the singleton value needs to be only one and very well known. A downside to using this pattern is that it is rather difficult to test.

Observer Pattern

The observer pattern is a very useful tool when we have a scenario where we need to improve the communication between disparate parts of our system in an optimized way. It promotes loose coupling between objects.

There are various versions of this pattern, but in its most basic form, we have two main parts of the pattern. The first is a subject and the second is observers.

A subject handles all of the operations regarding a certain topic that the observers subscribe to. These operations subscribe an observer to a certain topic, unsubscribe an observer from a certain topic, and notify observers about a certain topic when an event is published.

However, there is a variation of this pattern called the publisher/subscriber pattern, which I am going to use as an example in this section. The main difference between a classical observer pattern and the publisher/subscriber pattern is that publisher/subscriber promotes even more loose coupling then the observer pattern does.

In the observer pattern, the subject holds the references to the subscribed observers and calls methods directly from the objects themselves whereas, in the publisher/subscriber pattern, we have channels, which serve as a communication bridge between a subscriber and a publisher. The publisher fires an event and simply executes the callback function sent for that event.

I am going to display a short example of the publisher/subscriber pattern, but for those interested, a classic observer pattern example can be easily found online.

var publisherSubscriber = {};

(function(container) {

var id = 0;

container.subscribe = function(topic, f) {

if (!(topic in container)) {

container[topic] = [];

}

container[topic].push({

"id": ++id,

"callback": f

});

return id;

}

container.unsubscribe = function(topic, id) {

var subscribers = [];

for (var subscriber of container[topic]) {

if (subscriber.id !== id) {

subscribers.push(subscriber);

}

}

container[topic] = subscribers;

}

container.publish = function(topic, data) {

for (var subscriber of container[topic]) {

subscriber.callback(data);

}

}

})(publisherSubscriber);

var subscriptionID1 = publisherSubscriber.subscribe("mouseClicked", function(data) {

console.log("I am Bob's callback function for a mouse clicked event and this is my event data: " + JSON.stringify(data));

});

var subscriptionID2 = publisherSubscriber.subscribe("mouseHovered", function(data) {

console.log("I am Bob's callback function for a hovered mouse event and this is my event data: " + JSON.stringify(data));

});

var subscriptionID3 = publisherSubscriber.subscribe("mouseClicked", function(data) {

console.log("I am Alice's callback function for a mouse clicked event and this is my event data: " + JSON.stringify(data));

});

publisherSubscriber.publish("mouseClicked", {"data": "data1"});

publisherSubscriber.publish("mouseHovered", {"data": "data2"});

publisherSubscriber.unsubscribe("mouseClicked", subscriptionID3);

publisherSubscriber.publish("mouseClicked", {"data": "data1"});

publisherSubscriber.publish("mouseHovered", {"data": "data2"});

This design pattern is useful in situations when we need to perform multiple operations on a single event being fired. Imagine you have a scenario where we need to make multiple AJAX calls to a back-end service and then perform other AJAX calls depending on the result. You would have to nest the AJAX calls one within the other, possibly entering into a situation known as callback hell. Using the publisher/subscriber pattern is a much more elegant solution.

A downside to using this pattern is difficult testing of various parts of our system. There is no elegant way for us to know whether or not the subscribing parts of the system are behaving as expected.

We will briefly cover a pattern which is also very useful when talking about decoupled systems. When we have a scenario where multiple parts of a system need to communicate and be coordinated, perhaps a good solution would be to introduce a mediator.

A mediator is an object which is used as a central point for communication between disparate parts of a system and handles the workflow between them. Now, it is important to stress out that it handles workflow. Why is this important?

Because there is a large similarity with the publisher/subscriber pattern. You might ask yourself, OK, so these two patterns both help implement better communication between objects… What is the difference?

The difference is that a mediator handles the workflow, whereas the publisher/subscriber uses something called a “fire and forget” type of communication. The publisher/subscriber is simply an event aggregator, meaning it simply takes care of firing the events and letting the correct subscribers know which events were fired. The event aggregator does not care what happens once an event was fired, which is not the case with a mediator.

A nice example of a mediator is a wizard type of interface. Let’s say you have a large registration process for a system you have worked on. Oftentimes, when a lot of information is required from a user, it is a good practice to break this down into multiple steps.

This way, the code will be a lot cleaner (easier to maintain) and the user isn’t overwhelmed by the amount of information which is requested just in order to finish the registration. A mediator is an object which would handle the registration steps, taking into account different possible workflows that might happen due to the fact that each user could potentially have a unique registration process.

The obvious benefit from this design pattern is improved communication between different parts of a system, which now all communicate through the mediator and cleaner codebase.

A downside would be that now we have introduced a single point of failure into our system, meaning if our mediator fails, the entire system could stop working.

Prototype Pattern

As we have already mentioned throughout the article, JavaScript does not support classes in its native form. Inheritance between objects is implemented using prototype-based programming.

It enables us to create objects which can serve as a prototype for other objects being created. The prototype object is used as a blueprint for each object the constructor creates.

As we have already talked about this in the previous sections, let’s show a simple example of how this pattern might be used.

var personPrototype = {

sayHi: function() {

console.log("Hello, my name is " + this.name + ", and I am " + this.age);

},

sayBye: function() {

console.log("Bye Bye!");

}

};

function Person(name, age) {

name = name || "John Doe";

age = age || 26;

function constructorFunction(name, age) {

this.name = name;

this.age = age;

};

constructorFunction.prototype = personPrototype;

var instance = new constructorFunction(name, age);

return instance;

}

var person1 = Person();

var person2 = Person("Bob", 38);

person1.sayHi();

person2.sayHi();

Take notice how prototype inheritance makes a performance boost as well because both objects contain a reference to the functions which are implemented in the prototype itself, instead of in each of the objects.

Command Pattern

The command pattern is useful in cases when we want to decouple objects executing the commands from objects issuing the commands. For example, imagine a scenario where our application is using a large number of API service calls. Then, let’s say that the API services change. We would have to modify the code wherever the APIs that changed are called.

This would be a great place to implement an abstraction layer, which would separate the objects calling an API service from the objects which are telling them when to call the API service. This way, we avoid modification in all of the places where we have a need to call the service, but rather have to change only the objects which are making the call itself, which is only one place.

As with any other pattern, we have to know when exactly is there a real need for such a pattern. We need to be aware of the tradeoff we are making, as we are adding an additional abstraction layer over the API calls, which will reduce performance but potentially save a lot of time when we need to modify objects executing the commands.

var invoker = {

add: function(x, y) {

return x + y;

},

subtract: function(x, y) {

return x - y;

}

}

var manager = {

execute: function(name, args) {

if (name in invoker) {

return invoker[name].apply(invoker, [].slice.call(arguments, 1));

}

return false;

}

}

console.log(manager.execute("add", 3, 5));

console.log(manager.execute("subtract", 5, 3));

Facade Pattern

The facade pattern is used when we want to create an abstraction layer between what is shown publicly and what is implemented behind the curtain. It is used when an easier or simpler interface to an underlying object is desired.

A great example of this pattern would be selectors from DOM manipulation libraries such as jQuery, Dojo, or D3. You might have noticed using these libraries that they have very powerful selector features; you can write in complex queries such as:

jQuery(".parent .child div.span")

It simplifies the selection features a lot, and even though it seems simple on the surface, there is an entire complex logic implemented under the hood in order for this to work.

We also need to be aware of the performance-simplicity tradeoff. It is desirable to avoid extra complexity if it isn’t beneficial enough. In the case of the aforementioned libraries, the tradeoff was worth it, as they are all very successful libraries.

Next Steps

Design patterns are a very useful tool which any

senior JavaScript developer should be aware of. Knowing the specifics regarding design patterns could prove incredibly useful and save you a lot of time in any project’s lifecycle, especially the maintenance part. Modifying and maintaining systems written with the help of design patterns which are a good fit for the system’s needs could prove invaluable.

In order to keep the article relatively brief, we will not be displaying any more examples. For those interested, a great inspiration for this article came from the Gang of Four book Design Patterns: Elements of Reusable Object-Oriented Software and Addy Osmani’s Learning JavaScript Design Patterns. I highly recommend both books.