I do a lot of application design and architecture, and a rewrite project I'm heading up needed an architecture sufficiently designed to handle a set of complex requirements. What I was came up with is not new, and has been demoed and used many times before, but after a coworker told me he'd never heard of it, it occurred to me that I hadn't written a post about it yet, so here we are.

In this post, we'll be discussing the Repository-Service Pattern, a name I applied to a software architecture pattern that has been in use for quite some time. We'll take a look at how this pattern might be implemented in a real app, and discuss some advantages and one big disadvantage the pattern has.

Let's get started!

Overview

The Repository-Service pattern breaks up the business layer of the app into two distinct layers.

- The lower layer is the Repositories. These classes handle getting data into and out of our data store, with the important caveat that each Repository only works against a single Model class. So, if your models are Dogs, Cats, and Rats, you would have a Repository for each, the DogRepository would not call anything in the CatRepository, and so on.

- The upper layer is the Services. These classes can query multiple Repository classes and combine their data to form new, more complex business objects. Further, they introduce a layer of abstraction between the web application and the Repositories so that they can change more independently.

The Sample App Concept

Let's pretend we will model a day's sales and profits at a local movie theatre.

Movie theatres make money from two major sources: ticket sales and food sales. We want to build an app that can both display the tickets and food items sold, as well as generate some simple statistics about how much sales we had that day.

The Goals

By the end of this post, we will have a sample application which can do the following:

- Display all food items sold.

- Display all tickets sold.

- Display the average profit per ticket and average profit per food item on every page of the app.

The Sample Project

As with many of my blog posts, this one has a sample project over on GitHub that shows the complete code used. Check it out!

Building the Models

NOTE: This project is built in ASP.NET Core 3.0 using MVC architecture. All code samples in this post have been simplified. For the full code, check out the sample project on GitHub.

First, let's understand what kind of models we want to work with. Here's the sample model objects for a food item and a ticket:

public class FoodItem

{

public int ID { get; set; }

public string Name { get; set; }

public decimal SalePrice { get; set; }

public decimal UnitPrice { get; set; }

public int Quantity { get; set; }

public decimal Profit

{

get

{

return (SalePrice * Quantity) - (UnitPrice * Quantity);

}

}

}public class Ticket

{

public int ID { get; set; }

public string MovieName { get; set; }

public decimal SalePrice { get; set; }

public decimal StudioCutPercentage { get; set; }

public int Quantity { get; set; }

public decimal Profit

{

get

{

return (Quantity * SalePrice)

- (StudioCutPercentage * (Quantity * SalePrice));

}

}

public decimal ProfitPerItem

{

get

{

return SalePrice - (StudioCutPercentage * SalePrice);

}

}

}We will also need a simple model to represent the financial statistics:

public class FinancialStats

{

public decimal AverageTicketProfit { get; set; }

public decimal AverageFoodItemProfit { get; set; }

}With these models in place, we can start building the lowest layer of this pattern: the Repository layer.

Building the Repositories

The Repositories are intended to deal with operations for a single business model. This commonly includes CRUD functionality, and might also include more complex methods (e.g. querying for a collection of objects, or running stats against said collection).

It follows that because we have two business models, we need two repositories. Here's the repository for FoodItem:

public interface IFoodRepository

{

List<FoodItem> GetAllSold();

}

public class FoodRepository : IFoodRepository

{

public List<FoodItem> GetAllSold()

{

//In a real project, this is where you

//would call your database/datastore for this info

List<FoodItem> items = new List<FoodItem>()

{

new FoodItem()

{

ID = 14,

Name = "Milk Duds",

SalePrice = 4.99M,

UnitPrice = 1.69M,

Quantity = 43

},

new FoodItem()

{

ID = 3,

Name = "Sour Gummy Worms",

SalePrice = 4.89M,

UnitPrice = 1.13M,

Quantity = 319

},

new FoodItem()

{

ID = 18,

Name = "Large Soda",

SalePrice = 5.69M,

UnitPrice = 0.47M,

Quantity = 319

},

new FoodItem()

{

ID = 19,

Name = "X-Large Soda",

SalePrice = 6.19M,

UnitPrice = 0.59M,

Quantity = 252

},

new FoodItem()

{

ID = 1,

Name = "Large Popcorn",

SalePrice = 5.59M,

UnitPrice = 1.12M,

Quantity = 217

}

};

return items;

}

}The TicketRepository looks similar:

public interface ITicketRepository

{

List<Ticket> GetAllSold();

}

public class TicketRepository : ITicketRepository

{

public List<Ticket> GetAllSold()

{

List<Ticket> tickets = new List<Ticket>()

{

new Ticket()

{

ID = 1953772,

MovieName = "Joker",

SalePrice = 8.99M,

StudioCutPercentage = 0.75M,

Quantity = 419

},

new Ticket()

{

ID = 2817721,

MovieName = "Toy Story 4",

SalePrice = 7.99M,

StudioCutPercentage = 0.9M,

Quantity = 112

},

new Ticket()

{

ID = 2177492,

MovieName = "Hustlers",

SalePrice = 8.49M,

StudioCutPercentage = 0.67M,

Quantity = 51

},

new Ticket()

{

ID = 2747119,

MovieName = "Downton Abbey",

SalePrice = 8.99M,

StudioCutPercentage = 0.72M,

Quantity = 214

}

};

return tickets;

}

}There's nothing complex about these repositories; all they do is query the data store (in our case, the data store doesn't exist and we are mocking the results) and return objects. The real complexity starts in the next layer, where we will build the Service classes.

Building the Services

Recall that the Service classes are designed to do two things:

- Inherit from the Repository classes AND

- Implement their own functionality, which is only necessary when said functionality deals with more than one business object.

As of yet, the only functionality we have is getting the sold Tickets and Food for the day; it isn't very complicated. Consequently the TicketService and FoodService classes are very simple:

public interface IFoodService : IFoodRepository { }

public class FoodService : FoodRepository, IFoodService { }

public interface ITicketService : ITicketRepository { }

public class TicketService : TicketRepository, ITicketService { }But we need to keep in mind our Goal #3 from earlier, which is that we want to display the average item profit for both tickets and food items on every page of the app. In order to do this, we will need a method which queries both FoodItems and Tickets, and because the Repository-Service Pattern says Repositories cannot do this, we need to create a new Service for this functionality.

To accomplish this we need a new service class, one that queries both Food and Ticket repositories and constructs a complex object. Here's the new FinancialsService class and corresponding interface:

public interface IFinancialsService

{

FinancialStats GetStats();

}

public class FinancialsService : IFinancialsService

{

private readonly ITicketRepository _ticketRepo;

private readonly IFoodRepository _foodRepo;

public FinancialsService(ITicketRepository ticketRepo,

IFoodRepository foodRepo)

{

_ticketRepo = ticketRepo;

_foodRepo = foodRepo;

}

public FinancialStats GetStats()

{

FinancialStats stats = new FinancialStats();

var foodSold = _foodRepo.GetAllSold();

var ticketsSold = _ticketRepo.GetAllSold();

//Calculate Average Stats

stats.AverageTicketProfit =

ticketsSold.Sum(x => x.Profit) / ticketsSold.Sum(x => x.Quantity);

stats.AverageFoodItemProfit =

foodSold.Sum(x => x.Profit) / foodSold.Sum(x => x.Quantity);

return stats;

}

}That completes our Services layer! Next we will create the Controllers layer, which is to say, we will create a new ASP.NET Core Web App.

Building the Controllers

Here's a simple FoodController class (the corresponding view is on GitHub):

public class FoodController : Controller

{

private readonly IFoodService _foodService;

public FoodController(IFoodService foodService)

{

_foodService = foodService;

}

public IActionResult Index()

{

var itemsSold = _foodService.GetAllSold();

return View(itemsSold);

}

}The TicketController looks very similar:

public class TicketController : Controller

{

private readonly ITicketService _ticketService;

public TicketController(ITicketService ticketService)

{

_ticketService = ticketService;

}

public IActionResult Index()

{

var tickets = _ticketService.GetAllSold();

return View(tickets);

}

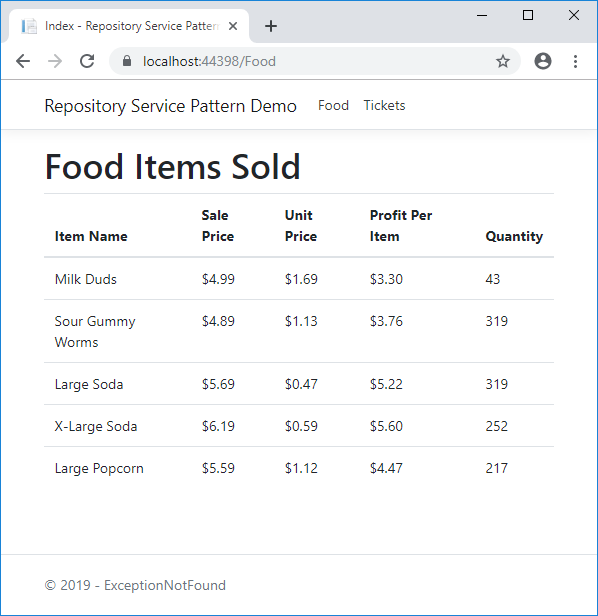

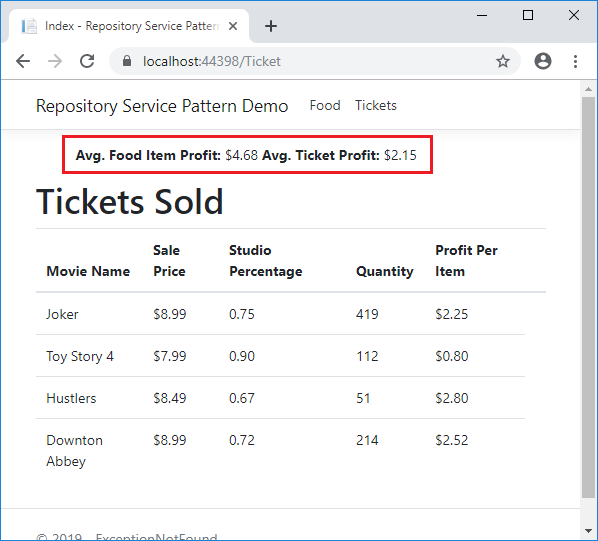

}These two controllers and their actions give us a way to see the Tickets and Food Items sold, which accomplishes two of our goals. Here's a screenshot of the Food Items page:

We still have our Goal #3 to do, though. In order to see these stats on every page, we're going to create a new View Component.

Building the FinancialStatsViewComponent

A View Component in ASP.NET Core MVC consists of multiple parts. The first and most important part is a class, which implements the ViewComponent class. Our class looks like this:

public class FinancialStatsViewComponent : ViewComponent

{

private readonly IFinancialsService _financialService;

public FinancialStatsViewComponent(IFinancialsService financialService)

{

_financialService = financialService;

}

public Task<IViewComponentResult> InvokeAsync()

{

var stats = _financialService.GetStats();

return Task.FromResult<IViewComponentResult>(View(stats));

}

}We also need a corresponding view, which will need to be located at ~/Views/Shared/Components/FinancialStats/Default.cshtml:

@model RepositoryServicePatternDemo.Core.Models.FinancialStats

<ul>

<li class="d-inline-block">

<strong>@Html.DisplayNameFor(x => x.AverageFoodItemProfit)</strong>

@Html.DisplayFor(x => x.AverageFoodItemProfit)

</li>

<li class="d-inline-block">

<strong>@Html.DisplayNameFor(x => x.AverageTicketProfit)</strong>

@Html.DisplayFor(x => x.AverageTicketProfit)

</li>

</ul>Finally, we need to invoke this component on the _Layout view:

...

<div class="container">

<main role="main" class="pb-3">

@await Component.InvokeAsync("FinancialStats")

@RenderBody()

</main>

</div>

...All of this results in the stats being visible on every page in the app, such as the Ticket Sales page:

Ta-da! We have accomplished out goals! Time to celebrate with some movie candy!

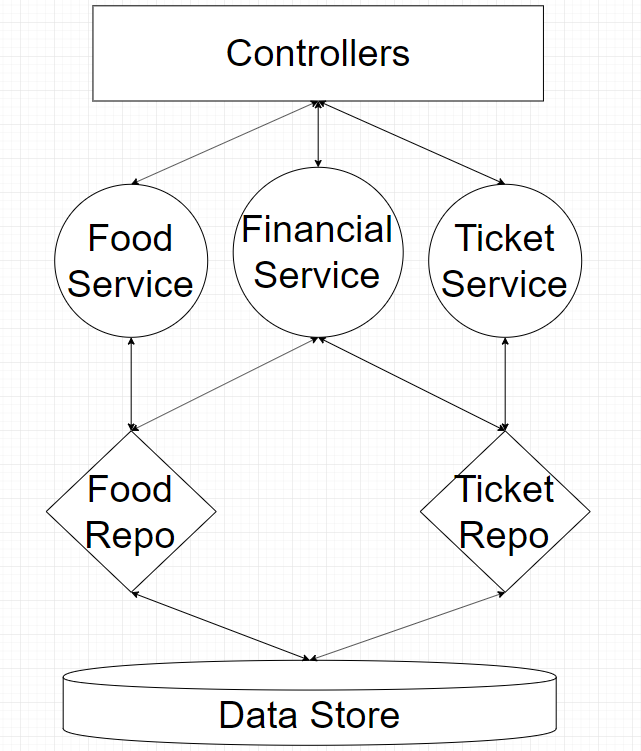

Architecture Diagram

Here's the architecture diagram for the project we ended up building:

The diagram points out the major benefit to using this pattern: clear and consistent separation between the layers of the architecture. This gives us the ability to change one layer with minimal impact to the others, and with clear direction as to what each layer contains, we can do so quickly and with a minimum of code.

Drawback of This Pattern

The Repository-Service Pattern is a great pattern for situations in which you need to query for data from a complex data store or need some layers of separation between what happens for single models vs combinations of models. That said, it has one primary drawback that needs to be taken into account.

That drawback is simply this: it's a LOT of code, some of which might be totally unnecessary. The TicketService and FoodService classes from earlier do nothing except inherit from their corresponding Repositories. You could just as easily remove these classes and have the Repositories injected into the Controllers.

I personally will argue that any real-world app will be sufficiently complicated so as to warrant the additional Service layer, but it's not a hill I'll die on.

Summary

The Repository-Service Pattern is a great way to architect a real-world, complex application. Each of the layers (Repository and Service) have a well defined set of concerns and abilities, and by keeping the layers intact we can create an easily-modified, maintainable program architecture. There is one major drawback, but in my opinion it doesn't impact the pattern enough to stop using it.

That's all for this post! Don't forget to check out the sample project over on GitHub! Also, feel free to ask questions or submit improvements either on the comments in this post or on the project repository. I would love to hear my dear readers' opinions on this pattern and how, or if, they are using it in their real-world apps.

Finally, if this post helped you learn about the usage of the Repository-Service pattern, please consider buying me a coffee. Your support funds all of my projects and helps me keep traditional ads off this site. Thank you very much!

Happy Coding!